I must acknowledge

From Swampland to Farmland: a history of the Koo Wee Rup Flood Protection District by David Roberts (Rural Water Commission, 1985); the chapter

Draining the Swamp in

The Good Country: Cranbourne Shire by Niel Gunson (F.W. Cheshire, 1968); and

Swamp Reclamation in Victoria by Lewis Ronald East, published in the Journal of the Institute of Engineers, Australia, March 1935, in the preparation of this history.

The Koo Wee Rup Swamp originally covered about 96, 000 acres (40,000 hectares) is part of the Western Port sunkland. Very non-scientifically, the land sunk thousands of years ago between the Heath Hill fault and the Tyabb fault, and the streams that originally drained straight to the sea, such as the Cardinia, Toomuc, Deep Creek, Ararat, Bunyip and Lang Lang then descended onto the flat sections of the sunkland, flowed out over the land and created the swamp conditions.

Small

scale drainage projects on the Swamp began as early as 1857 when William Lyall (1821

- 1888) began draining parts of the Yallock

Station to remove the excess water from the Yallock Creek. In 1867, Lyall and

Archibald McMillan, owner of Caldermeade,

funded a drain through the Tobin Yallock Swamp and created a drain to give the

Lang Lang River a direct outlet to the sea. Lyall also created drainage around Harewood house (on the South Gippsland

Highway Koo Wee Rup and Tooradin).

In

1875, landowners including Duncan MacGregor (1835 - 1916), who owned Dalmore, a property of over 3,800 acres

(1,500 hectares) formed the Koo Wee Rup Swamp Drainage Committee. From 1876 this

Committee employed over 100 men and created drains that would carry the water

from the Cardinia and Toomuc Creeks to Western Port Bay at Moody’s Inlet. The

Cardinia Creek outlet was eight metres at the surface, six metres at the base

and 1.2 metres deep, so no mean feat as it was all done manually. You can still

see these drains when you travel on Manks Road, between Lea Road and Rices Road

- the five bridges you cross span the Cardinia and Toomuc Creek canals (plus a

few catch drains)

It

soon became apparent that drainage works needed to be carried out on a large

scale if the Swamp was to be drained and landowners protected from floods. The

construction of the Railways also provided a push to drain the Swamp. The

Gippsland railway line, which straddled the northern part of the Swamp, was

completed from Melbourne to Sale in 1879. The construction of the Great

Southern Railway line through the Swamp and South Gippsland, to Port Albert, began

in 1887. These lines, plus a general demand for farm land bought the Government

into the picture.

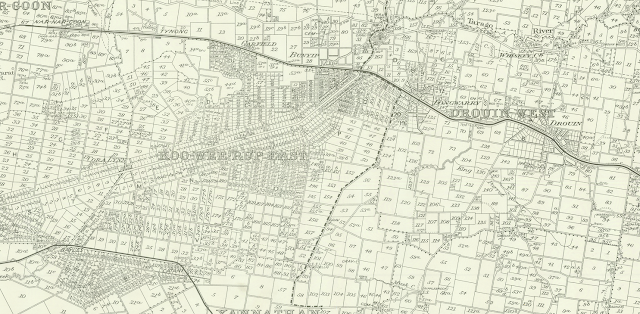

Plan showing flood protection and drainage works for Cardinia and Kooweerup Swamp lands: also watershed areas affecting same. State Rivers and Water Supply Commission, c. 1920s.

The

Chief Engineer of the Public Works Department, William Thwaites (1853 - 1907)

is almost forgotten in Swamp history, and should get more credit than he does.

Thwaites surveyed the Swamp in 1887 and his report recommended the construction

of the Bunyip Main Drain from where it entered the Swamp, in the north, to

Western Port Bay and a number of smaller side drains.

There was a scientific background to this scheme - Lewis Ronald East, engineer with and later Commissioner and then Chairman of the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission (SRWSC), in his 1935 paper Swamp Reclamation in Victoria in 1935 writes that the drainage plan was based on the formula Q=CM3/4 - where Q was the discharge in cusecs, C a coefficient and M the area of the area of the catchment in square miles. 50 was adopted as the value of C for ordinary floods and 100 for extraordinary floods. The Scheme was worked out in detail to deal with ordinary floods, but for some unaccountable reason - possibly shortage of funds - it was recommended that the drains be constructed in the first instance to only 1/3 of the designed dimensions, but the reserves were to be of sufficient width to allow future enlargement. East says that the intention of the “Swamp Board” was to merely facilitate the removal flood waters and thus permit the use of land between floods.

A tender for works was advertised in 1889. In spite of strikes, floods and bad weather by March, 1893, the private contractors had constructed the 16 miles of the drain from the Bay to the south of Bunyip and the Public Works Department considered the Swamp was now dry enough for settlement. At one time over 500 men were employed and all the work was done by hand, using axes, shovels, mattocks and wheel barrows.

This is the Main Drain (Bunyip River) - a 1940s postcard. The road bridge is at the front and

the rail bridge at the back

In spite of what seemed to be good progress - the Public Works Department had been unhappy with the rate of progress and took over its completion in 1893 and appointed, our friend, Carlo Catani (1852-1918) to oversee future works.

The

1890s was a time of economic depression in Australia and various Government

Schemes were implemented to provide employment and to stop the drift of the

unemployed to the city. One of these schemes was the Village Settlement Scheme.

The aim was for the settlers to find employment outside the city and to boost

their income from the sale of produce from their farms. It was in this context

that Catani implemented the Village Settlement Scheme on the swamp. Under this

Scheme, all workers had to be married, accept up to a 20 acre (8 hectares) block and

spend a fortnight working on the drains for wages and a fortnight improving

their block and maintaining adjoining drains. The villages were Koo Wee Rup,

Five Mile, Vervale, Iona and Yallock. The first 103 blocks under this scheme were allocated in April 1893.

Many of the settlers were unused to farming and hard physical labour, others were deterred by floods and ironically a drought that caused a bushfire. Many also relied on the wages they received for working on the drains, however this work finished in November 1897, so unless they could find other employment, or their farm was enormously successful they chose (or were forced by circumstance) to leave the Swamp. The Village Settlement Scheme on the Swamp was abandoned in 1899 and the land was opened for selection in the regular way.

My great grandfather, James Rouse, a

widower, arrived on the Swamp with his nine year old son Joe, in 1903. James,

who had been a market gardener in England, was part of a second wave of

settlers who were granted land as they had previous farming experience. By 1904, over 2,000 people including 1,400

children lived on the Swamp. By the 1920s, the area was producing one quarter

of Victorian potatoes and was also a major producer of dairy products. In fact,

as we know, Koo Wee Rup remains an important potato growing area and the

importance of the potato was celebrated by the Annual Potato Festival during

the 1970s and 1980s. Today, 93% of all Australian asparagus is produced on the Koo

Wee Rup Swamp.

The

existing drainage works that we see on the Swamp today are really the result of

a reaction to various floods. As East wrote in 1935 it was soon evident that the drainage provision made was quite

inadequate. There was a flood in

1893 and according to East the drains were enlarged by at least 50% in 1895 and

then enlarged again in 1902, the catalyst being the 1901 flood. The 1902 work had the objective to remove all

floodwaters from a maximum flood within three days

There

were some additional drains created in 1911 and by 1912 East says that the

drainage scheme had cost £234,000 and the Government had recouped only

£188,000. There were arguments over who should fund the scheme - many land

owners were opposed to being charged for any work and it was not until after

more floods in 1916 and 1917 they agreed in principle to an annual flood

protection charge and the ‘Lower Koo Wee Rup flood protection district’ came

into being.

The

State Rivers scheme provided for substantial remodelling and enlargement of

existing drains, new channels and additional drains next to the Main Drain to

take the water from the converging side drains. Other work carried out at this

time included giving the Lang Lang River a straight channel to the bay and at

the western end of Swamp tapping the Deep Creek into the Toomuc Drain created

in 1876.

The Lubecker Steam Dredge, imported by Carlo Catani, taken on May 21, 1914, the day the dredge was officially started. That is Carlo climbing down the ladder, see more photos of the dredge

here.

State Rivers & Water Supply Commission photographer, State Library of Victoria Image rwg/u855

Before

I go on to the devastating 1934 flood I am going to tell you briefly about the Lubecker Steam Dredge, which I have written about in more detail, here. Apparently Catani was interested in using machines on the Swamp

in the 1890s, but as this was a time of depression the Public Works Department

felt that this would take away jobs so it wasn’t until 1912 that Catani could

import his first dredge. It was the Lubecker Bucket Dredge, costing £4,716 which

arrived in May 1913 and started work on the Lang Lang River. When it finished there

in 1917 it started on the Koo Wee Rup Swamp on the Yallock Creek and other drains.

The now demolished Memorial Hall at Koo Wee Rup in the 1934 flood

Koo Wee Rup Swamp Historical Society photo

None

of the existing works could prepare the swamp for the 1934 flood. In

October of that year, Koo Wee Rup received over twice its average rain fall.

November also had well above average rainfall and heavy rain fell on December 1

across the State. This rainfall caused a flood of over 100,000 megalitres or

40,000 cusecs (cubic feet per second) per day. This was only an estimate

because all the gauges were washed away. The entire Swamp was inundated; water

was over 6 feet (2 metres) deep in the town of Koo Wee Rup, exacerbated by the

fact that the railway embankment held the water in the town; my grandparents

house at Cora Lynn had 3½ feet of water through it and according to family

legend they spent three days in the roof with a nine, five, three year old and

my father who was one at the time. Over a thousand people were left homeless.

This flood also affected other parts of the State, including Melbourne.

There

was outrage after the 1934 flood, directed at the SRWSC and it was even worse

when another flood, of about 25,000 megalitres (10,000 cusecs) hit in April,

1935. After this flood, 100 men were employed to enlarge the drains.

As

a result of the 1934 flood, the SRWC worked on new drainage plans for the Swamp

and these plans became known as the Lupson Report after the compiler, E.J

Lupson, an Engineer. A Royal Commission was also established in 1936. Its role

was to investigate the operation of the SRWSC. The Royal Commission report was

critical of the SRWSC’s operation in the Koo Wee Rup Flood Protection District

in a number of areas. It ordered that

new plans for drainage improvements needed to be established and presented to

an independent authority. Mr E. G Richie was appointed as the independent

authority. The Richie Report essentially considered that the Lupson Report was ‘sound

and well considered’ and should be implemented. Work had just begun on these

recommendations when the 1937 flood hit the area. The 1937 flood hit Koo Wee

Rup on October 18 and water

was two feet (60cm) deep in Rossiter Road and Station Street. The flood peaked

at 20,000 cusecs (50,000 megalitres) about half the 1934 flood volume.

The

main recommendation of the Lupson / Ritchie report was the construction of the

Yallock outfall drain from Cora Lynn, cutting across to Bayles and then

essentially following the line of the existing Yallock Creek to Western Port

Bay. The aim was to take any flood water directly to the sea so the Main Drain

could cope with the remaining water. The Yallock outfall drain was started in 1939

but the works were put on hold during World War Two and not completed until

1956-57. The Yallock outfall drain had been originally designed using the

existing farm land as a spillway ie the Main Drain would overflow onto existing

farmland and then find its own way to the Yallock outfall drain. Local farmers

were unhappy at this, as the total designated spillway area was 275 acres (110

hectares). They suggested a spillway or ford be constructed at Cora Lynn so the

flood water would divert to the outfall drain over the spillway. The spillway

was finally constructed in 1962. There is more on the Yallock Outfall drain, here.

Construction of the Spillway at Cora Lynn, October 1962 - the Main Drain is on the right, separated by a soon to be removed levee bank from the spillway which is ironically underwater, due to a flood.

Photo: Rouse family collection